By kcomnet

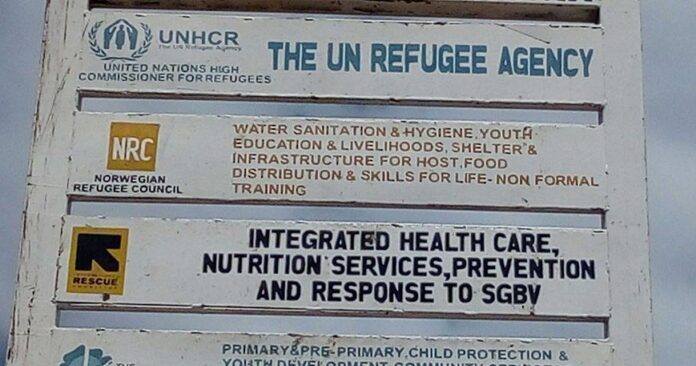

Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya has a population of over 147,000 refugees from 19 countries including South Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Burundi, Somalia, and the Democractic Republic of Congo. The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) states that the camp was established in 1992, along with the host community of Turkana, situated in the north-west region of the country.

The UNHCR in their latest global numbers released in June 2019, recorded that an unprecedented 70.8 million people around the world have been forced from their homes. This problem has added to the spread of misinformation in these communities that consist of people with various nationalities and beliefs. Kakuma refugee camp is no different.

In October 2019, Code for Africa (CfA) partnered with GIZ and KCOMNET in their UMOJA Radio for Peace project to train radio journalists from the Kakuma refugee camp, as well as from Turkana, Uganda and South Sudan. The project is focused on community radio actively engaging in conflict sensitive reporting in the pursuit of sustainable peace and development in Kenya.

This was one of many trainings by KCOMNET in their collective efforts for the development of community radio in Kenya. Each training session done across the country is a two-day event addressing fact-checking and content creation. CfA tackled fact-checking and verification while radio journalists Bande Edward, from Ratego radio, and Tebbi Otieno, from Mtaani radio, covered content creation.

Participants from the camp mentioned two instances of fake news:

During the country-wide Huduma number registration (National Integrated Identity Management System), different versions of misinformation were spread about the process, including that it was a satanic number received by the people. Peter Gatdeet, a pastor in the camp, said that because of that information some of his congregants decided to return home to Juba in fear of being indoctrinated into evil. Kanere news reflector, an independent news magazine produced by Ethiopian, Congolese, Ugandan, Rwandan, Somali, Sudanese and Kenyan journalists operating in Kakuma Refugee Camp, recorded some of these instances.

H.E President Uhuru Kenyata had to address the claims:

Leaders of different groups and nationalities in the camp falsely informed their members that another faction was planning to attack them, which resulted in the former attacking the latter group who had no ill intentions whatsoever. Such instances have happened often.

Also noted were clashes between the host community of Turkana and the refugees. The Kanere news reflector reported that, on July 10, armed conflict between Somali refugees and members of the host community resulted in at least three injuries, including that of a child.

During the training, participants learned what fake news is: this was defined as deliberate, targeted misinformation spread via traditional print and broadcast news media or online social media. They also learnt that these fell in the categories of Misinformation, which is false information shared with no intent to harm; Disinformation — false information knowingly shared to cause harm; and Malinformation, which is when genuine information is shared to cause harm, often by moving private information into the public sphere.

In addition, they were taught that the fake news trend is driven by propaganda, because different people have interests they want to push; by under-resourced journalism, which does not allow for fact-checking a story; and by desire for political influence (misinformation can be a powerful tool in a time as sensitive as an election), or profit (gain from advertisers or private gain if the perpetrators are paid to spread fake news).

To counter such messages the communicators that were gathered for the training were taught how to spot fake news:

- What is the source of the information? Were they official channels or gossip?

- What is the date the information was first shared? Old news is not always relevant in the current situation.

- What are the supporting sources of the information? Are said sources credible?

- Do you have any biases? Personal biases may cloud judgement.

They also learnt how to fact-check images, videos, social media and websites and were encouraged to address malinformation as soon as it arises.

At the end of the two-day training, the journalists from the camp as well as all the others present, were equipped to address and assuage situations brought about by the propagation of fake news. They also learnt to not be the ones repeating and spreading untruths, by double checking the information they receive and present in their jobs.

The verification training materials can be found at http://bit.ly/KakumaFCT

Code for Africa (CfA) is the continent’s largest federation of indigenous civic technology and open data laboratories with CfA labs in Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda and a further five affiliate labs in Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Morocco and Sierra Leone and funded projects in a further 12 countries. CfA manages the $1m/year innovateAFRICA.fund and $500,000/year impactAFRICA.fund, as well as key digital democracy resources such as the openAFRICA.net data portal and the GotToVote.cc election toolkit. CfA primarily supports grassroots citizen organisations and the media to help liberate data and empower citizens, but also works with progressive government agencies to improve digital service delivery.

In addition to funding and technology support, CfA’s labs incubate a series of trendsetting initiatives including the PesaCheck fact-checking initiative in East Africa, the continental africanDRONE network, and the African Network of Centres for Investigative Reporting (ANCIR) that spearheaded Panama Papers probes across the continent. CfA is an initiative of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).